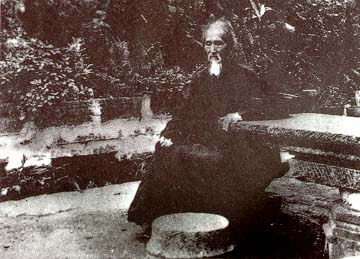

Biography of Master Xu Yun 1865 – 1959

Long before the time of his death in 1959 at the venerable age of 120 (95 ?) on Mount Yun-ju, Jiangxi Province, Master Xu-yun’s name was known and revered in every Chinese Buddhist temple and household, having become something of a living legend in his own time. His life and example has aroused the same mixture of awe and inspiration in the minds of Chinese Buddhists as does a Milarepa for the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, remarkable in view of the fact that Xu-yun lived well into our own era, tangibly displaying those spiritual powers that we must otherwise divine by looking back through the mists of time to the great Chan adepts of the Tang, Song and Ming Dynasties. They were great men whose example still inspires many today, but in many cases, we have scant details as to their lives as individuals, outside their recorded dialogues or talks of instruction.

The compelling thing about Xu-yun’s story which follows is that it paints a vivid portrait of one of China’s greatest Buddhist figures complete with all the chiaroscuro of human and spiritual experience. It is not a modern biography in the Western sense, it is true but it does lay bare the innermost thoughts and feelings of Master Xu-yun, making him seem that much more real to us. No doubt, the main thing for a Buddhist is the instructional talks, and Xu-yun’s are rich in insight, but it is only natural that we should wonder about the individual, human factors, asking what life was like for these fascinating figures. After all, holy men are like mountains, while their ‘peaks of attainment’ may thrust into unbounded space, they must rest on the broad earth like the rest of us. That part of their experience–how they relate to temporal conditions–is an intrinsic part of their development, even if the ultimate goal be to ‘pass beyond’ the pale of this world. In Xu-yun’s account we are given a fascinating glimpse into the inner life of a great Chinese Buddhist Master.

By the time of his passing, Xu-yun was justifiably recognised as the most eminent Han Chinese Buddhist in the ‘Middle Kingdom’. When he gave his talks of instruction at meditation meetings and transmitted the precepts in his final decades, literally hundreds of disciples converged upon the various temples where he met and received his followers and, on some occasions, this number swelled to thousands. Such a wave of renewed enthusiasm had not been witnessed in the Chinese monasteries since the Ming Dynasty when Master Han-shan (1546-1623) appeared. This eminent Master had also found the Dharma in decline and set about reconstructing the temples and reviving the teachings, as would Master Xu-yun some three hundred years or so later. Only years before these great gatherings around Master Xu-yun, many of the temples which he was subsequently to use had been little more than ruined shells, decrepit shadows of their former grandeur and vitality, but the Master revived these along with the teachings that were their very raison d’etre.

Not surprisingly, Xu-yun soon acquired the nickname ‘Hanshan come again’ or ‘Han-shan returned’, for their careers were in many respects similar. Both had shared the ordination name of ‘De-qing’ and both had restored the Monastery of Hui-neng at Cao-xi among others in their times. However, unlike his eminent predecessors in the Tang, Song and Ming Dynasties who had frequently enjoyed official patronage and support from Emperor and State, Xu-yun’s long life of 120 years spanned a most troublesome time both for China and Chinese Buddhism. It was a period continually punctuated by both civil and international conflict, with almost perpetual doubt and confusion as to China’s future and security, one in which general want and straitened circumstances were the order of the day.

Xu-yun was born in 1840 around the time of the Opium Wars and by 1843 the Treaty of Nanjing had been signed with the ceding of Hong Kong to Great Britain, the thin end of a wedge of foreign intervention in China’s affairs that was to have fateful and longlasting repercussions. Xu-yun lived to see the last five reigns of the Manchu Dynasty and its eventual collapse in 1911, the formation of the new Republican era taking place in the following year. With the passing of the old order, much was to change in China. China’s new leaders were not that concerned about the fate of Buddhism and indeed, many of them were inclined to regard it as a medieval superstition standing in the way of all social and economic progress. The waves of modernism sweeping China at this time were not at all sympathetic towards Buddhism nor any other traditional teachings. Needless to say, many of the monasteries found themselves falling on hard times and many others had already been in ruins before the fall of the dynasty. Government support for the Buddhist temples was scanty when not altogether absent. Of course, China’s new leaders had other things on their minds, for besides the frequent famines, droughts and epidemics which ravaged China during these years, there was also the growing threat of Japanese invasion. The Communist Chinese were rising in the countryside, soon to find sufficient strength to take on the Nationalist armies. By the late 1930s, Japanese troops occupied large areas of northern China. It goes without saying that this unfortunate social and political climate hardly offered the best of circumstances in which to embark upon large-scale renewal of the Chinese Buddhist tradition.

However, despite the odds stacked against him by dint of all this chaos, Xu-yun succeeded in retrieving Chinese Buddhism from abysmal decline and actually injected fresh vigour into it. In many ways, the story of Xu-yun is the story of the modern Chinese Buddhist revival, for by the end of his career, he had succeeded in rebuilding or restoring at least a score of the major Buddhist sites, including such famous places as the Yun-xi, Nan-hua, Yun-men and Zhen-ru monasteries, besides countless smaller temples, also founding numerous Buddhist schools and hospitals. His followers were scattered throughout the length and breadth of China, as well as in Malaysia and other outposts where Chinese Buddhism had taken root. During the Master’s visit to Thailand, the King became a personal disciple of Xu-yun, so impressed was he by the Master’s example. Xu-yun’s life-work would have been an achievement of note even during more auspicious days when official patronage had been freely given, but that this tenacious and devoted spirit succeeded in his aims amid the general want and turmoil of his times was even more remarkable and nothing short of miraculous. This was possible only because of the Master’s deep spiritual life, which alone could provide the energy for renewal amid confusion and decay. His external works were a reflection of the inner life he cultivated and one of a piece.

To many Chinese Buddhists, Xu-yun appeared like an incarnation and personal embodiment of all that was great about the Chinese Sangha in the halcyon days of the Tang and Song, and as a modern scholar in the West put it, Xu-yun ‘lived hagiography’, his life strangely infused with the spirit of greater times. The Master’s restoration work was often bidden in strange ways, as if a hidden reservoir of the whole Chinese Buddhist tradition wished to speak anew through his very being. When serving as Abbot of Gu-shan Monastery, Fujian, in 1934, the Master beheld the Sixth Chan Patriarch (d. 713) in his evening meditation. The Patriarch said, ‘It is time for you to go back.’ thinking that this betokened the end of his earthly career, the Master said a few words about it to his attendant in the morning and then put it out of mind. In the fourth month of that same year, he again beheld the Patriarch in a dream, who this time thrice urged him to ‘go back’. Shortly afterwards; the Master received a telegram from the provincial authorities in Guangdong, inviting him to take over and restore the Sixth Patriarch’s monastery at Cao-xi, then in just the same dilapidated condition as Han-shan had found it back in the Ming Dynasty before his own restoration work. Thus, Xu-yun handed over Gushan Monastery to another Abbot and proceeded to Cao-xi to set about restoring the famous Nan-hua Monastery, formerly known as ‘Bao-lin’ or ‘Precious Wood’, and from which the Chan Schools of yore had received their impetus and inspiration.

Throughout the Master’s long career, whether in good fortune or bad, he remained a simple and humble monk. Those who met him, including the usually more critical Western observers, found him to be thoroughly detached from his considerable achievements, unlike one or two other Chinese Buddhists who had welcomed publicity and self-glorification as instruments behind the Chinese Buddhist renaissance. While many talked, Xu-yun quietly went his way, as unaffected as the ‘uncarved block’ so dear to a wise Chinese heart. Again, despite the munificence of the temples he helped to restore, his noble simplicity remained entire. When the Master approached a holy site for restoration, he took a staff with him as his only possession; when he had seen his task completed, he left with that same staff as his sole possession. When he arrived at the Yun-ju mountain to restore the Zhen-ru Monastery, then a shambles, he took up residence in a cowshed. Despite the large sums of money which came in from devotees during restoration, the Master remained content with his simple cowshed and still preferred it, even after the Zhen-ru Monastery had risen, phoenix-like, from its ashes. But this was to be expected from a monk who had once lived on nothing but pine needles and water while on retreat in the mountain fastness of Gu-shan.

Famous, too, were the Master’s long pilgrimages on foot to holy sites at home and abroad, totally at the mercy of the elements and often with little more than his faith to support him. His greatest plgrimage began in his 43rd year when he set out for the isle of Putuo in Zhejiang, sacred to Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva. Carrying incense in hand, he prostrated every third step of the way to pay reverence to the ‘three gems’. Thence in a similar fashion, he headed for Mount Wu-tai in Shansi, sacred to Manjusri Bodhisattva, one point of his pilgrimage being to pay back the debt of gratitude he felt towards his parents; the strength of his determination can well be measured by the fact that he nearly perished twice in the bitter cold of Wu-tai’s snowy peaks but never gave up. He was saved by a beggar named Wen-ji, regarded by Chinese Buddhists as a ‘transformation-body’ of Manjusri. From Mount Wu-tai, the Master headed towards Tibet, which he visited, going on to Bhutan, India, Ceylon and Burma before returning to China via Yunnan, calling at holy sites en route.

During his travels the Master succeeded in realising ‘singleness of mind’ throughout day and night, so that by the time of his return to China, conditions were ripe for his final or complete enlightenment, which took place in his 56th year while at the Gao-min Monastery in Yangzhou. He was, as the Chinese say, one who had ‘ancient bones’, for as regards his later career of restoration which included reviving the teaching of the Five Chan Schools (Wu-jia), the Master was very much a ‘self-made man’ who had re-established these teachings on the strength of his own insight without teachers. A flash of the old insight was to be found here and there in the temples as Xu-yun had known them in his youth, but the Chan tradition had been in decline by and large. His first teachers had been either Dharma-Masters or Tian-tai Masters, though indeed his Tian-tai teacher had given him his first gong-an [Jap. koan] (‘Who is dragging this corpse about?’) and it would not be true to say that the Chinese temples had been totally lacking in enlightened individuals. The marked revival of the Chan tradition in the period extending from the mid-1930s through to the 1950s was largely attributable to Xu-yun’s endeavours.

The Master cared greatly for lay-Buddhists, too, and he was progressive for the way in which he opened up the temple doors to layfolk, teaching them alongside Sangha members. He made much of the pu-shuo or ‘free sermon’ end addressed all who came to him. Though a monk for 101 years, he never pretended that the Dharma was beyond the reach of layfolk. While his gathas and verses of instruction reveal the insight of one who saw beyond the pale of this world, he never failed to remind his disciples that the great bodhi is ever-present, always-there in our daily acts and seemingly mundane circumstances. Like all the great Masters of Chan before him, he laid stress on the non-abiding mind which is beyond reach of all conditioned relativities, even as they arise within it, a paradox that only the enlightened truly understand.

Though the Master became famous as a Chan adept, he also taught Pure Land Buddhism, which he considered to be equally effective as a method of self-cultivation, for like the hua-tou technique, the single-minded recitation of the Pure Land mantra stills the dualistic surface activity of the mind, enabling practitioners to perceive their inherent wisdom. This will surprise some Western people who tuned in to the ‘Zen craze’ a few years back, in which it was often said that Chan or Zen Masters eschewed use of the Pure Land practice. Also, contrary to what has been said on occasions, Xu-yun gave regular talks of instruction on the sutras and shastras, which he knew thoroughly after many decades of careful study and which he understood experientially, in a way which went beyond the grasp of mere words, names and terms in their literal sense.

By the time Xu-yun had rebuilt the physical and moral fabric of Chinese Buddhism, few of the disciples who gathered round the Master or attended the other temples he rebuilt had to suffer the same indignities and privations that he had experienced himself when calling at monasteries in his youth. He had often been turned away from temples that had fallen into the degenerate system of hereditary ownership, not even allowed a night’s lodging. When he had called at some temples, only a handful of monks were to be found because of the general decline. In one instance, famine had reduced the whole population of locals and monks at one site to just a single person who used to put on a ‘brave face’ if callers happened by. Given that kind of background, it is hardly surprising that Xu-yun recognised the need to recreate that self-sufficiency extolled by the ancient Master Bai-zhang Hui-hai (d. 814) in his famous dictum, ‘A day without work, a day without food’. Thus, wherever possible, Xu-yun revived the monastic agricultural system to live up to this tradition of self-sufficiency.

Thus far, all the necessary ingredients were present to sustain a revival which had borne fruit through decades of devoted effort. But we now come to a most tragic interlude in the life of Xu-yun which might well be called a ‘twilight of the gods’ were it the finale, though thankfully it was not. As is well known, the Communist Government took effective control of China in 1949 about the time that Xu-yun had set his aim on restoring the Yun-men Monastery in Guangdong. By 1951-52 the first tremors of what was to follow in the Cultural Revolution were beginning to make themselves felt. The restoration of the Yun-men Monastery was more or less complete, but misfortune struck from without with a purge of so-called ‘rightist elements’ in Guangdong Province. Being very much a ‘traditionalist’ in outlook, Master Xu-yun was an obvious target. Fears that Xu-yun might not be safe in the volatile atmosphere of these times had been voiced, the Master’s overseas disciples urging him to leave the mainland until things settled down. He refused to leave, however, expressly because he felt that it was his duty to look after the welfare of the monasteries. What happened next was almost inevitable; a horde of Communist cadres descended on the Yun-men Monastery which they surrounded. They locked the Master up in a room for several days, where he was interrogated and ruthlessly beaten, left for dead. Perhaps the less said about this episode, the better. Suffice it to say that the Master had broken ribs and bled profusely, being for a while most seriously ill. Remarkably enough though, while then in his 112th year, Xu-yun recovered from a beating severe enough to have killed someone less than half his age. This was not the first time that he had been beaten, for the police in Singapore had roughed him up back in 1916, ironically enough on the suspicion of being a ‘leftist’ from the mainland. But the beating he suffered in his 112th year was infinitely worse. Even so, without trying to make too little out of the violence he suffered, the old Master bounced back with all the properties of a proverbial ‘Daruma doll’ and lived to carry on teaching not only at the Yunmen Monastery but many others besides, also finding time and energy for one more round of restoration work at the Zhen-ru Monastery on Mount Yunju, Jiangxi Province, where he eventually departed from this world on 13 October 1959. He had been in the Sangha for 101 years.

With the Master’s passing in 1959, the Cultural Revolution was just around the corner. As we know, the monasteries had to suffer bitterly during that period. For many monks, nuns and lay devotees, it must have seemed that everything the Master had striven for was about to sink into oblivion. That draconian measures were already evident in Xu-yun’s last years must have caused him some concern; as it was, the episode at Yun-men cost him his most able disciple, Miao-yuan, who was executed. Other disciples had been harmed too. Things did look bleak, and even the news of events at Yun-men had to be smuggled out of mainland China by inserting records in the blank innerfolds of traditionally bound Chinese books. But as many on the mainland today are prepared to admit, the excesses of the Cultural Revolution were wrong; few would disagree.

Whether the long-term effects of ideological reform have been as catastrophic for Chinese Buddhism as once predicted is a good question. We should not deceive ourselves into thinking that Buddhism had been immune from persecution under the ancient regime. In the Hui-chang period (842-5) of the Tang Dynasty, a massive purge of Chinese Buddhism took place with the near destruction of some 4,600 monasteries, with 260,000 monks and nuns being forced back into lay life, the confiscation of monastic property and land being widespread. The monasteries managed to recover from that and by way of contrast, the modern picture is not entirely pessimistic. It is some consolation to learn that the temples which Xu-yun restored are not only being patched up after the ravages of the revolution, but that many are being restored to their proper use and once more assuming an air of normality, though the complement of monks and nuns is much smaller these days. At any rate, these are not the ‘actor monks’ shuffled around China by the authorities twenty years ago, who fooled nobody, but bona fide occupants. Of this I have been given reliable assurance from two sources, my friends Dharma-Master Hin-lik and Stephen Batchelor (Gelong Jhampa Thabkay), both of whom made recent visits to the monasteries in southern China.

Thus, rather than ending on a pessimistic note, we should rejoice in the fact that Xu-yun’s endeavours did not fall entirely on stony ground. Without the energies he released into Chinese Buddhism, it is quite likely that the Chinese Sangha would have suffered far greater setbacks than it did during the revolution. In this sense, Master Xu-yun lived out the mythical role of the ‘poison-eating peacock’ in Buddhist lore; from the bitterness of that poison something spiritual sprang forth. In the long run it seems that, as with the suppression of Buddhism in Tibet, the suppression of Chinese Buddhism has had the precise opposite effect to that intended by the suppressors. Not only has the Asian Buddhist had to reappraise the worth of the Dharma in his own context, but its merits have also struck the attention of the whole world.

Was it merely coincidence that at the height of the Cultural Revolution in China, copies of Lao-zi and Chan (Zen) texts went into record numbers of reprints in the West? Anyone at all familiar with the Jungian theory of synchronicity would find it hard not to see this phenomenon as a profound act of compensation in the collective psyche. Some things are meant to be and cannot be destroyed. Though all outward signs and symbols may be denied for a while, their inner archetypes always remain and, like seeds, they reassert themselves. It is salutary to note in this respect that no lesser person than the late C. G. Jung was reading Xu-yun’s Dharma-discourses while on his death-bed.

May all beings attain release!

UPASAKA WEN SHU (RICHARD HUNN)

Tholpe Hamlet, Norwich. 13 October 1987. The Anniversary of Xu-yun’s Nirvana.

Source : Richard Hunn, from Empty Cloud: The Autobiography of the Chinese Zen Master